To enlarge the image simply click on it.

The quality of ink is perhaps the main reasons a Scroll will last 2,000 years or 100 years.

The main ingredients for ink acceptable in writing Torah Scrolls and other articles that have the same standard are: Water, Oak Gall Nut, Gum Arabic, Soot, Logwood, Copper Sulfate or Iron Sulfate. There are many recipes for this ink and many laws the Scribe must follow to produce kosher ink. There is a recent movement among Soferim to stop including the sulfate, either iron or copper, in the ink. They are giving two reasons for this decision. First, the commandment that no product ever used for war, including iron and copper, can be used in writing a Sefer Torah. The second reason is the quick decay of the scroll, 150 years maximum, due to iron gall ink degradation. Many Soferim are simply going back to the soot base ink. It is the sulfate that causes the chemical reaction which results in the degradation of the ink and it is the quality and amount of gum Arabic that causes the ink to crack and fall off the letters.

Ink used in writing STaM (Scrolls, Tfillin, Mezuzah) is called D’yo. Some recipes found in the Talmud call for an ink using the recipe found here, but boiled down to a paste. Then whenever the scribe was ready to write he simply dropped the ink wafer into a small quantity of water containing gall and used the ink in the same fashion we use water colors today. We have a scroll where perhaps this was the method used and on this scroll we have found places where the quantity of tannic acid was so high that over a period of time holes were burned through the parchment.

The owner of Pergamena, the parchment craftsman in the Hudson Valley New York, said that the reason for the flaking letters was due to a change in the ink recipe. The owner of the company said when paper began to be used widely that the iron gall ink had too much gall, tannic acid, in the recipe and it quickly ate holes in the paper.

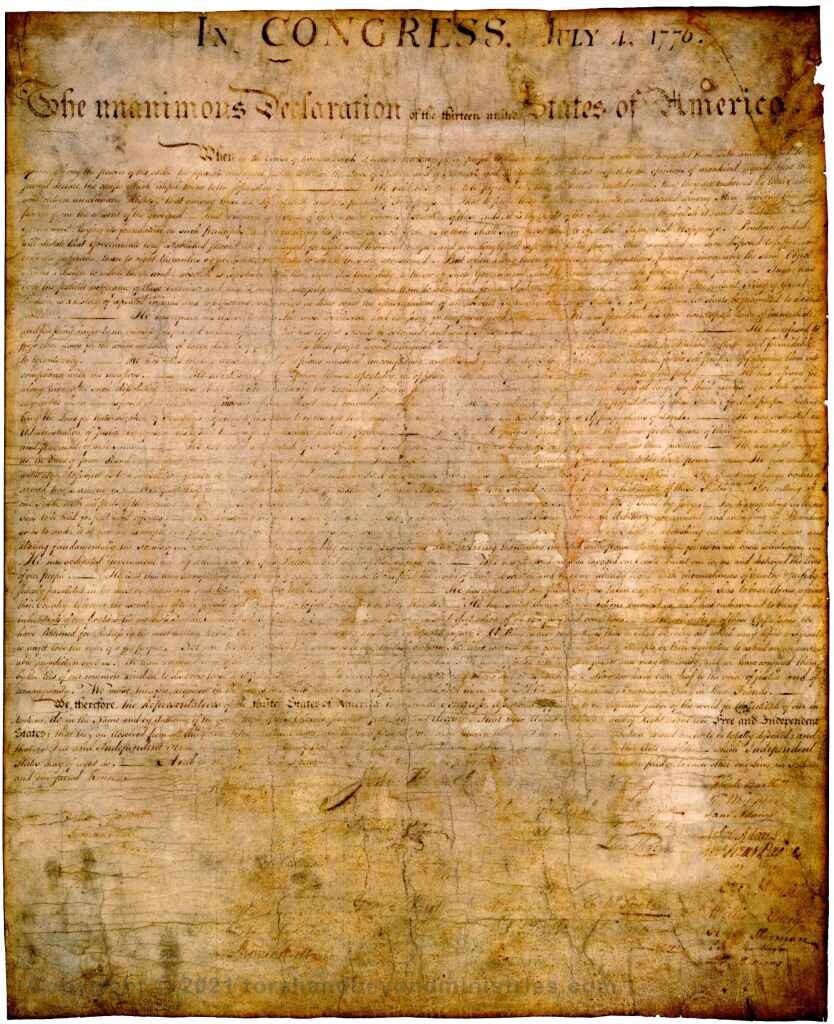

Iron Gall ink has proved to be the ink of choice for the last 2,000 years among the Scribes. This ink has been found in the manuscripts from the caves of Qumran to the modern calligrapher in the 21st century. It was the ink of choice for Leonardo da Vinci, Bach, Rembrandt and Van Gogh. The Constitution of the United States, the Bill of Rights and Declaration of Independence were penned with this ink.

When the ink on the Dead Sea Scrolls was analyzed using a cyclotron at the Davis campus of the University of California, there were three recipes for the ink. One was the carbon base gall ink; the other was the iron gall ink. The difference in the two is Iron-gall ink burned into the parchment by reacting with collagen in the skin.

The third type of ink was found in a few scrolls at Qumran. It was called “red ink”. After analysis it proved that mercury sulfate was used rather than iron or copper sulfate. This is a very rare occurrence. Also, in the writings of China it is recorded that among the Jews in ancient time they were in possession of a “Red Torah”. Very little is known about this Torah other than it was red. Perhaps the ink was red because the Chinese used mercury in many religious ceremonies and the Jews used it also in their ink. Perhaps the scroll came from the region around Babylon where it was common to write scrolls on deer skin. Usually deer skin scrolls will turn red with age.

A high-quality ink has long been made from the Aleppo gall, found on oaks in the Middle East. The galls are formed when a gall wasp lays eggs on the leaves of oak trees. The hatched larvae feed upon the tree, secreting an irritant that prompts the tree to create a growth around the larva. The gall provides both food and protection for the larva. After the larva has developed into a wasp, it chews its way out of the gall. Small holes in galls indicate where the insect has made its escape. Wasps that have not made it out can sometimes still be found inside the galls once cracked open. When the larva or insect is still inside the gall, the tannin content is said to be higher than if the insect has escaped. The galls I purchase are very high quality and most do not have holes in them indication the wasp never hatched.

STaM (Scrolls, Tfillin, Mezuzah) ink has a very simple recipe, but it is critical that there is a strict control in quantity and purity of the elements involved.

By mixing powdered gall nuts which is high in tannic acid with copper sulfate or iron sulfate, a water soluble tannate complex is formed. In general, the color of a freshly made iron, or copper gall ink solution is pale thus the soot is added for a ready black ink.

Acacia Senegal tree – Sudan exported 26,000 metric tons of gum Arabic in 2000

Gum Arabic can be purchased in a large crystal form, natural, or powdered by the gram or by the Kilo from Kremer Pigments New York.

www.kremerpigments.com

Kosher ink is rather difficult for the average person to buy, because the proper ink is so critical only a few Soferim are trusted to make it. If you wish to try to make it there are several recipes for making ink, though all seem to revolve around the same basic set of ingredients.

Basic formula for ink

(The following recipe is from the International Stam Forum stamforum.com/2012/03/dyo-making.html

This will produce about 2 quarts of fine, durable ink.

3 oz oak galls

1 oz logwood shavings

2.2 oz gum arabic

1.9 oz copperas

The trick to making really, really good iron gall ink is long, slow cooking of the galls and logwood. Some recipes I’ve seen call for just tossing all four ingredients together in a jar of water and allowing it to ‘macerate’ for a few weeks. This is great if you want to write with a disappointingly grey ink. However, if you’re like me and want an rich, deep black ink, straight from the bottle then we need to prepare the ingredients a bit more.

Stage One:

Assemble, weigh and prepare the ingredients for cooking.

Be sure to use containers specifically designated for non-food use. There’s a good chance that these ingredients will leave a residue that would not be so good to ingest. So just like our meat and dairy dishes, we keep our ink pans separate.

We’ll be using one ounce of logwood to make this ink. Be sure to get the good stuff for this. The best logwood comes from the heartwood carefully planed into shavings. This grade costs about five dollars an ounce, but is much stronger and more light-fast than cheaper varieties. To prepare the logwood, it needs to be soaked overnight. Use enough water to saturate and cover the wood shavings, but there’s no need to go crazy and use a fifty gallon drum for one ounce of logwood. A small Rubbermaid dish will be perfectly adequate.

Soaking the logwood overnight is an essential part of the process. Do not skip it or you will achieve inferior results. In the picture above you can see that the logwood has turned the water a deep, reddish colour. It is this property that gives the logwood it’s scientific name Haematoxylum, which means ‘blood wood’ in Greek.

Now on to the oak galls. We need three ounces. As with everything here weigh accurately!

As you can see it doesn’t take many, 59 galls in total, all of them smaller than an acorn. If we estimate that it takes something on the order of half a pint of ink to write a Torah scroll and that there are eight pints to a gallon, and that this recipe makes 1/2 gallon, then with just these 59 oak galls we could write 8 Torah scrolls! Not bad for a little wasp.

As one cannot simply write with oak galls in their solid state, we need to crush them coarsely in preparation for cooking. I find it easiest to simply use a pair of nutcrackers. Be warned, the galls are incredibly hard! You could easily hit them hard with a hammer repeatedly and experience no result, or else no result that was afterwords retrievable.

Now, if you’re feeling terribly Medieval, as I was, you may of course proceed to grind them to a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. Otherwise, you may feel free to use a spice mill.

In any event, which ever course of reduction you choose, it should become a powder. It may be wise during this stage to wear some type of protective mask, as you wouldn’t want to inadvertently breathe in powdered oak gall, it does after all contain gallo-tannic acid. From experience I can confirm that the dust does irritate the respiratory passages.

Once done, the powder should be put in a suitable container and covered with hot water, which we will allow to steep overnight. We have begun to extract the tannins in the oak galls.

At this point the logwood and the oak galls have been reduced finely and soaked in hot water over night. We are now ready to begin the cooking process. The cooking process involves three separate boilings. In the first, take the galls and the logwood and put them into a 4 quart stainless steel pan and add four cups of water, distilled if possible. Chlorine, flouride, salts and minerals in tap water do funny things to ink over time.

First Boiling: Over a medium fire, boil the galls and logwood for one hour. Replenish any liquid lost to evaporation. Strain the liquor and set it aside.

Second Boiling: Using the same galls and logwood add 2 1/2 cups of water and boil for half an hour. Strain the liquor and add it to the first.

Third Boiling: This time add only 1 1/2 cups of water to the galls and logwood. Boil for half an hour, and add to the rest. Allow the whole lot to cool and steep over night.

The next day, using a bit of flannel, filter the liquor into a separate container. Then squeeze the galls to extract whatever potency they may have left.

The liquor as you can see has turned a very deep brown. If it comes in contact with your skin it will leave it looking quite orange and shiny. Add water if necessary to make up the full two quarts. Using a pitcher marked for quarts is useful at this stage.

The next day, I measured out the 1.9 ounces of copperas and crushed the 2.2. ounces of gum arabic to powder then dissolved it in about 1/2 cup of hot water.

Return the gall liquor to the fire and heat it until it is quite hot. Then add the copperas and stir vigorously. The dark brown of the galls will turn deep black in seconds as the chemical reaction between the gallo-tannic acid and the ferrous sulphate takes place. Then pour in the tincture of gum arabic and stir.

This change took place in about 3 seconds.

In theory, you could begin writing with this ink immediately, however, I would recommend letting it age a bit. Leave the pan uncovered for a couple of days stirring occasionally. Oxidisation does seem to improve the the darkness of the ink.”

Iron Gall Ink Degradation

Ink degradation has been major problem with the Soferim for the past several hundred years. The ink on Scrolls will either flake off, fade to a light brown color, or holes will appear over letters.

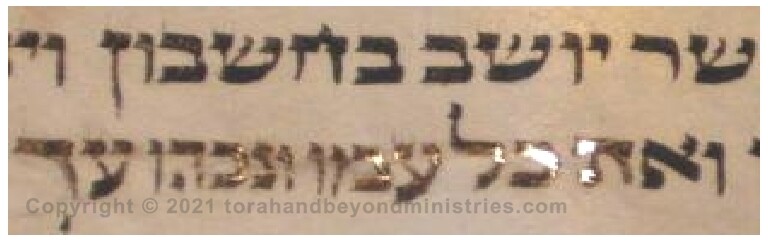

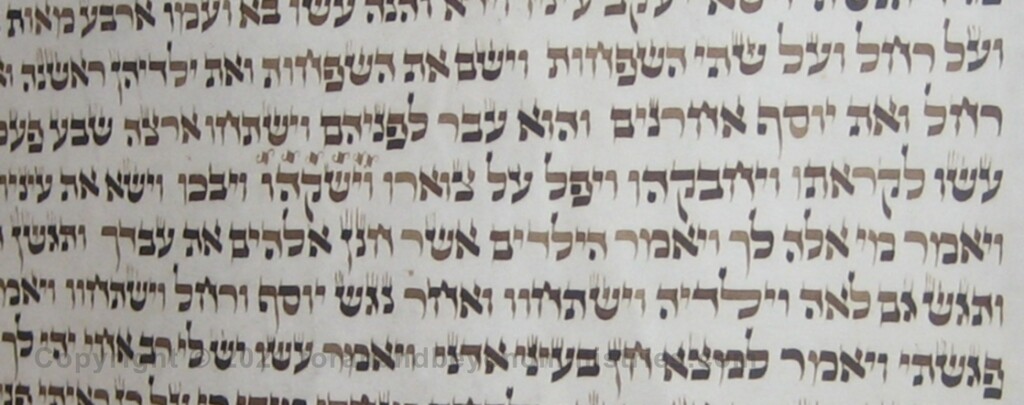

Observe the very light ink on some letters and the darker ink on others. This Torah Scroll was re-lettered sometime in the past to keep it kosher and now it is nearing the point where it can no longer be repaired.

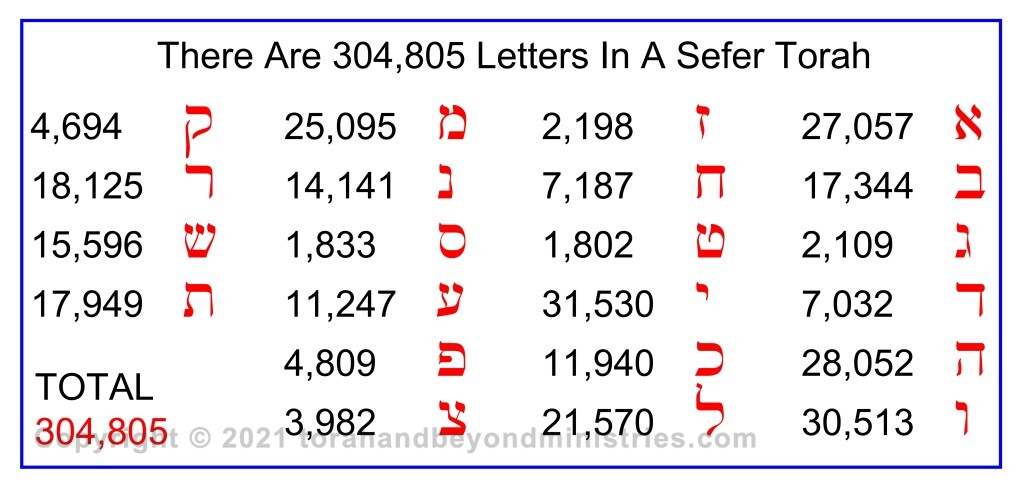

Observe the Sofer re-lettering this Torah Scroll. It is easy to see in the shiny part of letters above the quill. There are 305,805 Hebrew letters in a Torah Scroll. If one is not kosher the Scroll becomes pasul, not kosher. It is more profitable to re-letter thousands of letters rather than to write a new Torah.

What difference does it make?

Noah xn

This is the Hebrew spelling of the one who built the ark to save mankind during the Flood. Suppose 3,000 years ago part of the first letter n was damaged and the bottom of the letter could not be seen. The Hebrew word would then become:

Yich xy

We would all be telling the story of Yich and the Ark.

Jesus said in Matthew Mt 5:18 For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled.

When Jesus said one Jot or one Tittle would not pass from the Torah he was making reference to the Yod (JOT) the most common letter used 31,530 times in the Torah and the Tet (TITTLE) the least common letter used 1,820 times in the Torah. Some people will say the Jot and Tittle are the taggin or the foot or crown on a letter. Others say they are the cantillation, trope markings in the Tikkun.

The problem is not only with Hebrew Scrolls but also the libraries of the world and governmental archives have been searching for ways to preserve writing and drawings on animal skin documents. Observe the condition of the ink on the Declaration of Independence. The ink has degraded to the point that it is almost illegible.

The following is a copy of some correspondence I had with Dr. Scott Carroll, a teacher of ancient manuscripts concerning the degradation of iron gall ink on scrolls.

“I have a few questions concerning the stability of the ink on the early manuscripts you are examination. When you have time I would appreciate your observations.

Have you noticed a lot of re-inking on the letters as we find in the Hebrew scrolls? Our oldest Hebrew scrolls, 1300s and 1400s both have fairly stable ink, but the scrolls from the 1700s and 1800s all show quite a bit of re-inking broken letters. It does not seem to matter if the scrolls are from Italy, Hungary, Lithuania etc. I have been told by Pergamena, the parchment craftsman in the Hudson Valley New York, said that the reason for the flaking letters was due to a change in the ink recipe. The owner of the company said when paper began to be used widely that the iron gall ink had too much gall, tannic acid, in the recipe and it quickly ate holes in the paper. If the people who cooked the ink for the manuscripts did not know the consequences in the reduction of gall on parchment this could be a possibility. I have handled quite a few scrolls and it seems like it took about 100 years for the ink to start falling off the scrolls to the extent that re-lettering became necessary. The ones using the new recipe would not be aware of the problem in their lifetime.

So my question is: is the ink stable on your manuscripts? Secondly, have you heard of the change in iron gall ink recipe and do you think this could be the problem with 1700 and 1800 scrolls?”

This following is a picture of the galls that are found in the southern parts of the United States. Perhaps you have found them lying on the ground around your house. They are mostly hollow and would be a poor substitute for the galls coming from the Middle East.